My mother was an

English and German translator. When my parents had to leave their positions,

due to German orders in 1941 forbidding Jews most work, they worked in

the administration of Jewish children’s homes of the UGIF.

Between 1940 and 1941, fleeing the German invasion, like

many families, we left the Paris area (we lived in Issy-les-Moulineaux),

and stayed in different cities, notably in Eure-en-Loir, then in Royan.

I don’t have a good memory of our journey.

At the beginning of July 1943, my parents sent me off

to the countryside, near Châteauroux (Indre) with my younger sister,

for summer vacation. We stayed with a former household employee of my

maternal grandmother, who was living a well deserved retirement with her

husband. She had seen me born, took care of me during my early years,

and we were equally happy to see each other again. Our mother had removed

the yellow stars from our coats, and my sister and I had changed our name.

We took the name “Bernard”, our mother’s maiden name. My other sister

had stayed in Paris, because she was thought too young to leave her parents

My mother was arrested July 31, 1943, in a round-up in

the UGIF offices. She stayed a few weeks in Drancy, and was

deported to Auschwitz by Convoy No. 59 on September 2, 1943. According

to one person arrested at the same time as she, and who survived, she

was gassed on her arrival.

After the arrest of my mother, my father had to hide the

youngest of my sisters with a family in the countryside. The couple that

was lodging my other sister and me gladly accepted keeping us with them

until further instructions. At the beginning of the new school year, in

October 1943, they enrolled us in the village’s school.

My father, who had

remained in Paris, hid at a friend’s, in an apartment. He was sure that

he should never have to go out. But this voluntary confinement weighed

heavily on him, and Tuesday, April 11, 1944, he went out into the street.

From later years, a document about his arrest came to us: toward noon,

a French collaborator, André H., age 35, saw him on a sidewalk.

My father’s face appeared suspect to this man, who gave the order to arrest

him immediately. The identification check which likely followed proved

fatal to him. He was taken to Drancy, where he remained

until May 15, 1944, when he left by Convoy No. 73.

The police report on the French collaborator who had arrested

my father, brought to light only in his cross-examination, cited my father’s

name and described the circumstances of his arrest. This man, condemned

twice in his absence to the death penalty (in 1944 and 1949) for treason

or conspiring with the enemy, had escaped to Germany in August 1944, and

presented himself, a free man, February 16, 1955, before the Permanent

Tribunal of the Armed Forces of Paris.

The person who passed this police report on to us added

at the time, “He was acquitted in 1957, and walks free, maybe cultivates

flowers ….”.

My sister and I led a trouble-free and peaceful life,

cared tenderly by our protectors. We had quickly forgotten the restrictions,

the vile Jerusalem artichokes and the insipid rutabagas, for we lacked

nothing: garden vegetables, grapes and fruits of the vine, chicken, rabbit,

milk and fresh butter.… We had all we wanted and were happy, thanks to

the complicity of the adults, family and friends who, at the request of

our father and in the efforts to spare us, had not told us that our mother

had been deported. We learned it one day, following a slip by our guardian.

But at that time, they did not talk about deportation; they only told

us that our mother had been “arrested”, and since we didn’t know exactly

what that meant, we calmly awaited her return.

After the arrest of our father, a cousin arrived from Paris

while we were at school. He was still there at noon, when we came home

for lunch. He had come to tell us that our father too was just “arrested”,

and that we had to leave our guardians for a few days, in case the Germans

would be looking for us. We didn’t really understand the seriousness of

the situation. All we knew about the little move they were preparing us

for was that we would spend two or three weeks on a farm, a few kilometers

from where we were, among animals and farm work, without going back to

school, and that delighted us.

When the alarm passed, we went back to the village we had

left, and stayed there until December 1944.

A little before Christmas 1944, our maternal grandfather

and our aunt had us return to Paris. They did what was necessary to be

able to welcome us in their home, all three of us together. The youngest

of my sisters returned first to Paris. Hidden for a year with the family

with whom my father had entrusted her, she had been unhappy, even mistreated,

but at least she had been saved.

My other sister and I left with regret the old couple

who had sheltered us for eighteen months, without doubt—as paradoxical

as that might seem at first—the happiest period of my whole life. I had

never realized, until these past few years, and even these past weeks,

from learning the personal story of each of my “cousins” of “trips through

memory” in Lithuania, how these brave people had saved our lives, my sister’s

and mine

Later, in 1998, I requested that they be honored with

the recognition as “Righteous Gentiles—Righteous among the Nations.” I

had to look for witnesses from the time when I was hidden in Levroux,

in friendly Berry, and I found, fifty years after losing contact with

them, some classmates who were glad to give me their assistance. May I

thank here Jeanne, Monique, and Jean-Paul, in the name of Françoise,

like Alain, who will receive the award in the name of his great-aunt and

great-uncle, Mr. and Mrs. Couagnon, my rescuers.

|

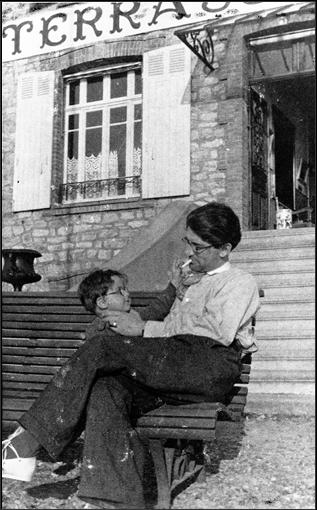

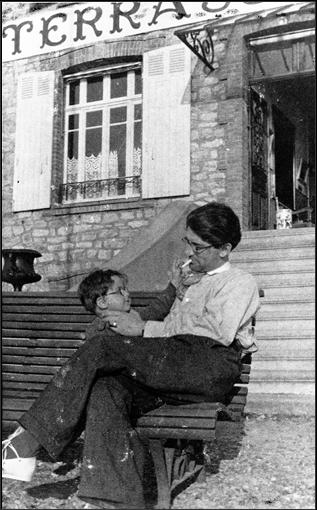

I

love that photo, showing my father and I, in Summer 1936. My hair were

short cutted because I just had whooping cough with much fever. My two

sisters haven't any such a photo and are very jealous... I have now another

photo, which shows one of my grandsons, Antoine, aged six, taken when

he is about three. He looks exactly as myself at the same age !

|

Our

aunt became our “guardian”. She was an admirable woman, who had entered

the Resistance very early, where her actions earned her the Medal of the

Resistance and the Cross of War 1939-1945. She raised us with much tenderness

and devotion, without ever complaining about the sudden arrival of three

little girls — of seven, ten, and thirteen years — completely changing

her whole life. My sisters and I owe her a lot, indisputably, for all

she did for us, in every area and on all occasions, well after she stopped

serving as guardian. When we left her home, she continued to come to the

aid of each of us three, in one way or another, each time it was necessary,

likewise to our children when, as teens, they in their turn had difficulties,

until age and illness prevented her. She left us in May 1997, at the age

of 93.

I learned soon after from my aunt that my mother had died

in Auschwitz. Looking back, she never spoke about our father to us, and

we never asked questions. There was a tacit silence, which lasted fifty

years. However, my aunt had contact with some of the survivors of Convoy

No. 73, for I found in 1997, after her death, their names that she had

noted on a card

In 1952, totally by chance I met André Blum, who

would become my husband the following year. His father had been deported

to Auschwitz in 1942 by Convoy No. 35, on September 21. He had been arrested

September 2nd, on André’s birthday. This similarity in the destiny

of our fathers helped me, without a doubt, endure more calmly and less

painfully the consequences of the disappearance of my parents when I became

aware of it, fifty years later, which was not the case for my two sisters.

In 1992, by chance during genealogical research that my

husband and I had begun that year, I learned of the existence of the Mémorial

de la Déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial of the Deportation

of the Jews of France) by Serge Klarsfeld, and thus I learned what had

happened to my father. Destiny had his life end about a hundred kilometers

from the city where his grandmother was born, in that Lithuania from which

his grandparents and parents had fled a century earlier ….

Descendants of my parents number today eleven grandchildren

and nineteen great-grandchildren, of whom fifteen are the children of

my children! The oldest, Eric, was born in 1979, and Sarah, the youngest,

arrived in 1997, the first day of spring.

Eve Line Blum-Cherchevsky

|

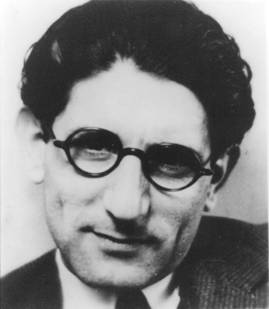

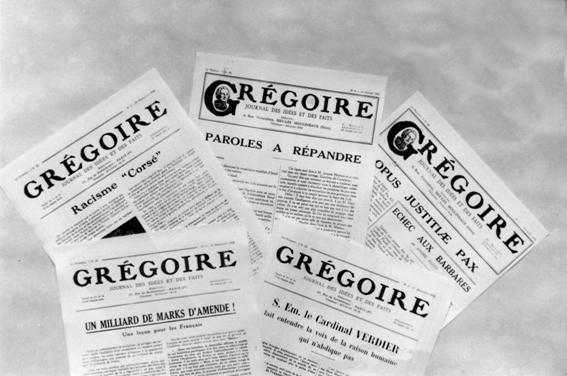

Bernard Lazare

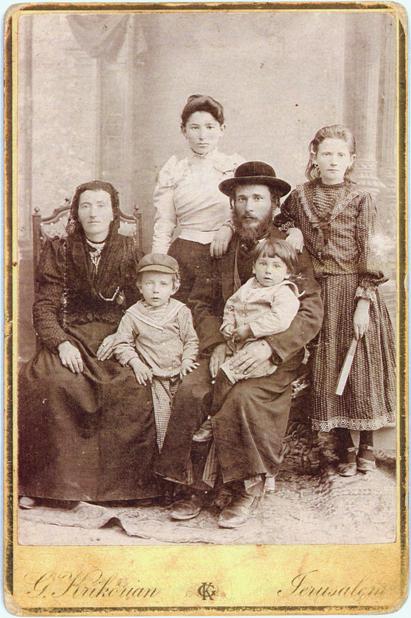

(1865-1903) : my mother, Germaine Cherchevsky nee Bernard. You certainly

heard of the Dreyfus Affair. In this affair, the first Jew who said that

Alfred Dreyfus was not guilty was a Bernard Lazare. In reality his name

was Lazare BERNARD, and he was my mother's uncle, her father's brother. |